THE INDEPENDENT: Bad Grandpa: When Jackass was nominated for an Oscar...

Bad Grandpa: When Jackass was nominated for an Oscar...

The make-up and hair team of Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa have been nominated for an Oscar

“The producer overheard a 10-year-old kid saying, ‘Dad, that’s Johnny Knoxville.’ His dad didn’t believe him. It turned out the dad was a doctor!” Bryan Christensen

In Bad Grandpa, the latest movie from the Jackass stable, an 86-year-old named Irving Zisman takes a kooky, cross-country road trip with his young grandson. Along the way, the pair shock, unnerve and offend a succession of unsuspecting bystanders, before making a subversive appearance at a child beauty pageant. So far, so Little Miss Sunshine.

Yet what sets the former film apart from its influences is that the witnesses to its wacky set-pieces are not actors but real people, and Zisman is played not by a real eightysomething, but by Johnny Knoxville, who is 42. That his elderly disguise was so convincing explains why Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa is this year’s most unlikely Oscar nominee, in the Make-up and Hairstyling category.

Tony Gardner, one of the make-up special- effects specialists behind Zisman, says, “If the make-up doesn’t work, the movie doesn’t work. Most of the time comedies aren’t recognised [by the Academy Awards]. But the platform that this film’s make-up stands on is the fact that the character worked in the real world, in real light, in front of real people.”

Alterian’s HQ is a warehouse on a non-descript industrial estate in the unremarkable LA suburb of Irwindale. But hidden behind its beige facade is a workshop filled with weird creations coming to life, and an office decorated with previous on-screen triumphs: a dog in a full-body plaster cast from There’s Something About Mary; John Travolta’s female fat-suit from Hairspray; the titular robot from the sci-fi dramedy Robot & Frank. One memento sadly missing is a 14-foot replica of David Hasselhoff that the firm made for The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie – now being used as the base of a glass-top table at the Hoff’s home.

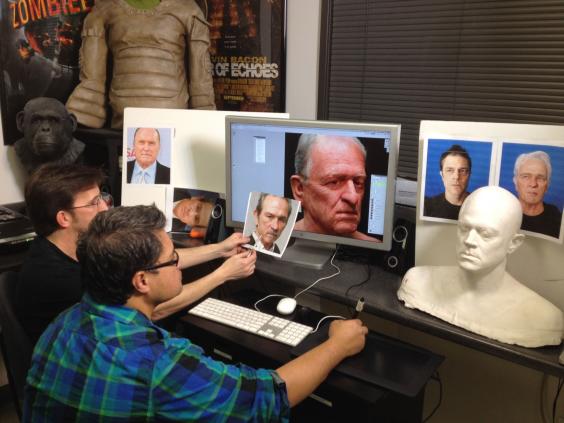

Turning heads: Tony Gardner and Lilo Tauvao work on ideas for ‘Bad Grandpa’ (Bryan Christensen)

Irving Zisman’s features were based in large part on Gardner’s grandfather, Fred. The face was made from silicone, paper-thin and translucent. The ears and the back of the head were latex. Then there was the wig, the eyebrows, the moustache, the dental veneers, and the liver-spotted backs of his hands. The team also made a wrinkled torso for Knoxville to wear in scenes where he removed his shirt, as well as some other anatomical items that it would be inappropriate to describe in the pages of a family newspaper. Each make-up element had to be mass-produced so that Knoxville could be disguised anew for every day of the 60-day shoot.

Remarkably, his cover was rarely blown. “There was a scene when he went to a Jacuzzi and dropped a colostomy bag in the water,” Gardner explains. “The producer overheard a 10-year-old kid turning to his dad and saying, ‘Dad, that’s Johnny Knoxville.’ His dad didn’t believe him – he said: ‘Look at all the wrinkles on his stomach. It’s a real guy.’ It turned out the dad was a doctor!”

Gardner, who is 50, grew up in Ohio but moved to California in the 1980s to study film at USC. Ostensibly as part of his studies, he engineered a meeting with legendary special-effects man Rick Baker, who offered him a four-week job as a production runner. “Four weeks turned into four years,” Gardner says. He subsequently worked with Baker on projects as varied as the music video for Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Gorillas in the Mist, and established his own company while working on the cult horror The Return of the Living Dead in 1985.

One of the key members of the Jackass gang is writer-director Spike Jonze, whom Gardner met while working on David O Russell’s Gulf War movie Three Kings, in 1999. “Spike was one of the people I was doing make-up on,” Gardner recalls. “He kept saying, ‘I’ve got to get back and edit my movie.’ I was like, ‘Oh God, this is one of those actors who wants to be a director.’ But we really hit it off, and it turned out later that he was in the middle of editing Being John Malkovich.”

Gardner worked on Jonze’s second film, Adaptation, and then Jonze introduced him to Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo and Thomas Bangalter, better known as the enigmatic French dance duo Daft Punk. Alterian was instrumental in the design of the helmets worn by the band for their public appearances. Gardner and Bangalter bonded over a shared love for the 1950s sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, and the helmets were influenced by the Gort, that movie’s alien robot.

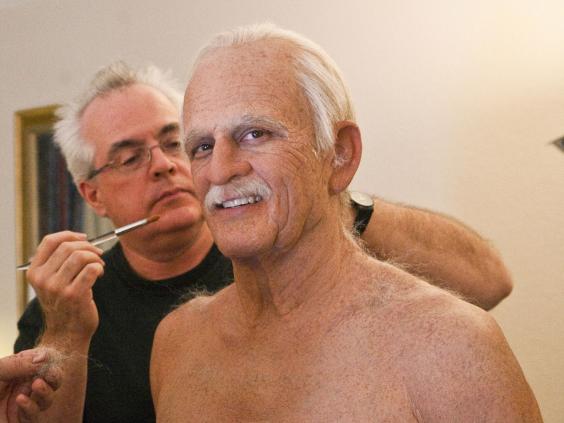

Bart Mixon works on Johnny Knoxville’s make-up (Sean Cliver)

Alterian recently completed work on the comedy sequel Dumb and Dumber To, though the firm’s relationship with gross-out auteurs the Farrelly Brothers stretches back to There’s Something About Mary in 1998. “I had little kids at the time and I was taking phone-calls at home that involved asking people things like, ‘The sperm on Ben Stiller’s ear: is it clear or white? How long is it? Is it chunky? The boobs: do you want her nipples out or down? The balls in the zipper: do you want veins?’ These are not conversations you want your kids to hear!”

Today, the SFX industry is under threat from the rise of its rival, VFX, and Gardner explains that where Alterian might once have made creature suits for actors, film-makers now just cover their actors in coloured dots and add the creatures as post-production CGI. Though the company specialises in overweight and old-age make-up such as Zisman’s, even that business is being usurped. “There are films being shot as we speak, with younger actors playing older, and they’re experimenting with dots and digital make-up instead of physical.”

For the real-life survival drama 127 Hours, Alterian made the fake arm that James Franco sawed off using a blunt penknife. The prosthetic was so anatomically convincing that Gardner has started a side business creating life-like babies and combat wounds to help train emergency room doctors and army medics.

And yet, he says, manufacturing believable make-up is only half the battle. “Half the success of make-up is the person wearing it. With James Franco, the arm was great, but if he hadn’t made it real, you wouldn’t have bought it. We can make Johnny Knoxville look 80-something, but if he doesn’t own it and sell you on it, you’re not going to buy it. It’s a collaboration.”

LOS ANGELES TIMES | ENTERTAINMENT: “Addams Family Values,” How did they do that? Featuring Tony Gardner and Alterian Inc.

The Sleight of Hand in 'Addams' : Movies: How did they do that? Tony Gardner's Alterian Studios was responsible for much of the special effects in 'Values.' It's all a matter of 'illusion,' he says.

Wednesday Addams is standing against the wall at Alterian Studios. As soon as her wig comes back from the production company, Wednesday will join Darkman, the Tommyknocker and a life-size hippo on permanent display of Alterian's most beloved children.

Much of the special-effects work that Tony Gardner's Alterian Studios did for "Addams Family Values" ended up as "blink and you'll miss it" moments in the film, but if you don't blink, you'll go home wondering, "How did they do that?"

And that's just the reaction Gardner hopes for.

"I think it all goes back to starting as a magician," Gardner said. "The whole thing was the illusion and being able to fool somebody."

Gardner, now 30, got his start apprenticing with three Academy Award-winning special effects artists--Rick Baker, Stan Winston and Greg Cannon (who won for his work on "Bram Stoker's Dracula"). Two particular illusions Gardner created with his studio stand out in "Addams Family Values": Wednesday's blending into the woodwork--literally--and Baby What, Cousin Itt's new offspring.

For the scene in which Wednesday (Christina Ricci) camouflages herself as part of a wall to spy on the sinister new nanny, Debbie (Joan Cusack), Gardner and his crew had to make a full body cast of Ricci and manufacture a stand-in dummy. Instead of needing two hours to be put into full makeup, Ricci could simply lean into the dummy's fake neck, leaving only her face needing to be made up.

Gardner didn't have to worry about dealing with a potentially prickly actor with Baby What: the tyke is entirely mechanical. There were other challenges, though. The guidelines he received from director Barry Sonnenfeld and visual effects supervisor Alan Munro: "Here's a ball of fur: make it cute, make it happy, make kids want to relate to it, make adults think it's precious and want to hold it, and . . . good luck."

The resulting Baby What gets one of the biggest laughs in the movie, but more rewarding to Gardner was the reaction of the film's crew. "I think the reward," he says, "really comes from going on set and taking something that's a bunch of motors and foam wrapped over fiberglass, creating something that's alive and watching a film crew--probably your most jaded audience in existence, because they've seen it all--get excited about it, whether there's a person in it or not."

Gardner's studios also built the miniatures that stand in for the Addams house and Uncle Fester's new house ("We called it Debbie's Dream House" for the nanny character played by Cusack, who plots to wed Fester). The Addams house is in many shots, but Debbie's Dream House was built for one main purpose--to blow up.

"It was designed to explode and obliterate itself instantaneously, like a Looney Tunes cartoon," Gardner said.

Though called a miniature, the exploding house was actually 16 feet tall and 28 feet long, taking up a large chunk of the warehouse where Alterian is situated, in Irwindale.

"Everyone had to work around it and walk around it," Gardner said. "(Then) all this stuff drives out to the set one day on a Friday and they come back on Monday with two milk crates"--all that was left of Debbie's Dream House. Even the tables the house was built on were destroyed.

The house wasn't hard to build, Gardner says, because "we'd done a lot of exploding bodies in the past and we were able to use a lot of the existing technologies for it," and there was a certain amount of professional satisfaction in those two milk crates.

As a child, Gardner might have had a premonition about the line of work he would eventually end up in. He was fascinated by the magic set his grandparents bought him when he was 6.

"I picked up this box where you put a card in and it's got a fake bottom and (the card) falls. Well, I picked it up without reading the instructions, put a card in it, closed it and opened it and the card was gone. . . . Then I turned it over and I shook it and the card fell out from the fake bottom. Then I got it. I was like, 'It's fake! It's not real!'--and I was hooked."